Regina Taylor’s Crowns: The Overflow of “Memories Cupped under the Brim”

Artisia Green

Abstract

In crossing the cultural border between the North and the South, Yolanda, the main character in Regina Taylor’s Crowns, is sent on both a physical and metaphysical journey that symbolizes the ideology of the Kongo Cosmogram. South Carolina, Yolanda’s landing point and the play’s geographical context, bears multiple implications for the dramaturgy of Crowns. The land is saturated with memories of the African presence due to slave importation patterns within the coastal Sea Islands and low-country post–Civil War settlement by formerly enslaved people of West Africa and the Caribbean. As such Yorùbá aesthetics and theoretical ideas of the self are evident in the characterizations in Crowns, and Gullah culture shapes its dramatic structure. Taylor employs a dramaturgy of the “mother tongue”—the use of ideological and aesthetic elements (language, rites, “myths, rhythms, and cosmic sensibilities”) (Harrison 1974, 5) of a pre–Trans-Atlantic history—to provide continuity across the oceans and between the river of the living and the departed; to foster healing, order, and liberation in Yolanda’s state of dis-ease and chaos; and to illumine her soul (Ford 1999, 5; Marsh-Lockett and West 2013, 3).

“[U]nlike the Western idea of art, African art is not produced solely for aesthetic ends. It is not art for art’s sake but deeply reflects certain accepted truths and shared values at the same time reinforcing and symbolizing them” (Ademuleya 2007, 217).

“The truth that was lost in the morning comes home in the evening” (Unknown).

Adapted from the photo-essay book Crowns: Portraits of Black Women in Church Hats (2000) by photographer Michael Cunningham and oral historian Craig Marberry, Crowns, the gospel musical, has become one of the most widely produced musicals in America since its McCarter Theatre premiere in 2002. Regina Taylor’s critically acclaimed adaptation concerns seventeen year old Yolanda, a culturally unaware and increasingly self-sabotaging young woman who is sent south to live with her grandmother, Mother Shaw, following her brother’s murder at the hand of his friend. After enlisting the aid of her compatriots—First Lady Mabel; Velma, a funeral director; Jeanette, a working mother; Wanda, the youngest Hat Queen but, no less adept in the rules of fashion; and Man, the church minister—they present for Yolanda, according to scholar Velma Love, what anthropologists Elizabeth Fine and Jean Haskell Speer consider an “epistemological verbal performance.” This type of performance demonstrates identity through the artful and repeated telling of stories of self and community (Love 2012, 10). In the range of personal stories that are shared about themselves, their loved ones, and other role models, Crowns promotes dress and head ornamentation as a technology of self-narration (Foucault 1988, 18), adornment through which individuals can beautify themselves, assert their individuality, and communicate cultural knowledge. The play is a communal examination of identity through epistemic testimonials to which Yolanda is mostly a “silent witness.” The testimonials serve to expand her worldview, which suffocates in the urbanity of her youth, and help her “open up and deal with her present condition, her feelings of loss and rootlessness…and [help] her to see a brighter future for herself” (Taylor 2005, 4).

Adapted from the photo-essay book Crowns: Portraits of Black Women in Church Hats (2000) by photographer Michael Cunningham and oral historian Craig Marberry, Crowns, the gospel musical, has become one of the most widely produced musicals in America since its McCarter Theatre premiere in 2002. Regina Taylor’s critically acclaimed adaptation concerns seventeen year old Yolanda, a culturally unaware and increasingly self-sabotaging young woman who is sent south to live with her grandmother, Mother Shaw, following her brother’s murder at the hand of his friend. After enlisting the aid of her compatriots—First Lady Mabel; Velma, a funeral director; Jeanette, a working mother; Wanda, the youngest Hat Queen but, no less adept in the rules of fashion; and Man, the church minister—they present for Yolanda, according to scholar Velma Love, what anthropologists Elizabeth Fine and Jean Haskell Speer consider an “epistemological verbal performance.” This type of performance demonstrates identity through the artful and repeated telling of stories of self and community (Love 2012, 10). In the range of personal stories that are shared about themselves, their loved ones, and other role models, Crowns promotes dress and head ornamentation as a technology of self-narration (Foucault 1988, 18), adornment through which individuals can beautify themselves, assert their individuality, and communicate cultural knowledge. The play is a communal examination of identity through epistemic testimonials to which Yolanda is mostly a “silent witness.” The testimonials serve to expand her worldview, which suffocates in the urbanity of her youth, and help her “open up and deal with her present condition, her feelings of loss and rootlessness…and [help] her to see a brighter future for herself” (Taylor 2005, 4).

The act of remembering and the performance of memory is a key component of the dramaturgy of this play. Characters maintain and communicate tradition largely through their recollection and performance of memory. Liedeke Plate and Anneke Smelik posit in Performing Memory in Art and Popular Culture that “memory is always re-call and re-collection, and consequently, it implies re-turn, re-vision, re-enactment, re-presentation: making experiences from the past present again in the form of narratives, images, sensations, [and] performances” (2013, 6). In Crowns hats are like artifacts: the performance of buying, receiving, retrieving, and seeing, and/or wearing one opens a floodgate of memories which are subsequently performed in the present and passed down for maintenance in the future. At times memory is performed subconsciously as observed by Yolanda, who at the close of the play reminds us that “African Americans do very African things without even knowing it. Adorning the head is one of those things” (Taylor 43).

Taylor’s adaptation of Crowns is a form of performance that triggers and transmits memory. Reading the play recalls aesthetic elements from other 20thcentury artists who inspired Taylor’s own artistic career. In an online interview with Ebony magazine, she attributed the play’s quilt-like feel to the collage work of Romare Bearden, who fashioned images of African American life through layering and stitching together elements of the sacred and secular, the past and present (Admin2012b). Traces of homage to another of Taylor’s contemporaries, Ntozake Shange, are also evident in Crowns. The play bears similarities to Shange’s choreopoem, for colored girls…. Both plays utilize seven characters fashioned after archetypes, noted by attributes and color, and both contain a string of parabolic monologues interspersed with music, dance and ensemble interludes.

Taylor, who purchased her first crown for the McCarter Theatre opening and then subsequently wore that same hat to her mother’s funeral, memorializes her mother in the play:

I was at my mother’s house telling her about my research and what I was discovering, and she took me to her closet to show me her hats. Each hat had a story: a wedding, a funeral, a baptism—a marker in her life. Then she walked me back through them again and each hat had another story. I learned so much about my mother that day that I had never known before; all these memories cupped under the brim. (Palmer 2012, 2–3)

This essay enters with the goal of examining the multiple “memories cupped under the [play’s] brim.”

Melvin Rahming’s “critical theory of spirit” (2013, 36) frames the play’s text to elucidate elements critical to the dramaturgy of Crowns. In crossing the cultural border between the North and the South, Yolanda is sent on both a physical and metaphysical journey that symbolizes the ideology of the Kongo Cosmogram. South Carolina, Yolanda’s landing point and the play’s geographical context, bears multiple implications for the dramaturgy of Crowns. The land is saturated with memories of the African presence due to slave importation patterns within the coastal Sea Islands and low-country post–Civil War settlement by formerly enslaved people of West Africa and the Caribbean. As such Yoruba aesthetics and theoretical ideas of the self are evident in the characterizations in Crowns, and Gullah culture shapes its dramatic structure. Taylor employs a dramaturgy of the “mother tongue”—the use of ideological and aesthetic elements (language, rites, “myths, rhythms, and cosmic sensibilities”) (Harrison 1974, 5) of a pre–Trans-Atlantic history—to provide continuity across the oceans and between the river of the living and the departed; to foster healing, order, and liberation in Yolanda’s state of dis-ease and chaos; and to illumine her soul (Ford 1999, 5; Marsh-Lockett and West 2013, 3).

Methodology

Christian and Yoruban cultural and spiritual expressions are embodied in my personal life and at times my theatrical work; I am therefore sensitive to the dramaturgy of an artist and writer that speaks to the invisible and esoteric forces that intersect with and stimulate our realities. Melvin Rahming’s critical theory of spirit is a methodological approach to textual analysis of works with spirit—“the infinite, self-conscious force or energy that originates, drives, and perpetually interrelates everything in the universe”—at their center (2013, 36). Rahming acknowledges that the model is both “critical” and “subjective” because while it recognizes theoretical and aesthetic markers of a given spiritual paradigm, it is greatly concerned with how “the text engages and potentially enriches the spirit of the reader” (37). Rahming identifies the three characteristics of a spirit-centered work: (1) the text embodies the idea that everything—“materials, objects, ideas, elements, emotions, attitudes, perspectives, frequencies, cells, vibration, etc.”—is interrelated; (2) the text conjures up and presents “spiritual conditions and spiritual activity”; and (3) the text conveys an underlying spiritual milieu (37). Rahming’s theory proves useful in illuminating African-centered spiritual undertones which find expression in the text. As James Padilioni Jr., ethnographer and graduate student at the College of William and Mary, stated, “I saw the idea behind Crowns and that immediately screamed Yoruba to me.”[1] James, much like myself, was engaged by the play’s African spiritual consciousness—an insight that begins with the title, which alludes to notions of the Orí (the physical head or conscious self) and kariocha (having one’s head spiritually crowned with an Orisha). Artist and art historian, Michael Harris says that “the aesthetic of secrecy in African art . . . the divine intent . . . the àṣẹ [becomes] visible to the initiate, when you move beyond that which keeps people occupied and discuss the real of what’s going on”.[2] This analysis, which speaks to the text’s latent spiritual dramaturgy, will begin with the Yoruba aesthetic and theoretical ideas that bear on Crowns as a result of the play’s geographical context.

Christian and Yoruban cultural and spiritual expressions are embodied in my personal life and at times my theatrical work; I am therefore sensitive to the dramaturgy of an artist and writer that speaks to the invisible and esoteric forces that intersect with and stimulate our realities. Melvin Rahming’s critical theory of spirit is a methodological approach to textual analysis of works with spirit—“the infinite, self-conscious force or energy that originates, drives, and perpetually interrelates everything in the universe”—at their center (2013, 36). Rahming acknowledges that the model is both “critical” and “subjective” because while it recognizes theoretical and aesthetic markers of a given spiritual paradigm, it is greatly concerned with how “the text engages and potentially enriches the spirit of the reader” (37). Rahming identifies the three characteristics of a spirit-centered work: (1) the text embodies the idea that everything—“materials, objects, ideas, elements, emotions, attitudes, perspectives, frequencies, cells, vibration, etc.”—is interrelated; (2) the text conjures up and presents “spiritual conditions and spiritual activity”; and (3) the text conveys an underlying spiritual milieu (37). Rahming’s theory proves useful in illuminating African-centered spiritual undertones which find expression in the text. As James Padilioni Jr., ethnographer and graduate student at the College of William and Mary, stated, “I saw the idea behind Crowns and that immediately screamed Yoruba to me.”[1] James, much like myself, was engaged by the play’s African spiritual consciousness—an insight that begins with the title, which alludes to notions of the Orí (the physical head or conscious self) and kariocha (having one’s head spiritually crowned with an Orisha). Artist and art historian, Michael Harris says that “the aesthetic of secrecy in African art . . . the divine intent . . . the àṣẹ [becomes] visible to the initiate, when you move beyond that which keeps people occupied and discuss the real of what’s going on”.[2] This analysis, which speaks to the text’s latent spiritual dramaturgy, will begin with the Yoruba aesthetic and theoretical ideas that bear on Crowns as a result of the play’s geographical context.

Crossroads and Other Geographic Considerations

From Robert Thompson’s work on the African Bakongo culture in Flash of the Spirit, we learn that the Kongo Cosmogram (Yowa Cross), or cruciform signification within the circle formed from the movement of the sun, speaks to the cyclical nature of an individual’s life amongst the intersection of the cross’s lines. The Bakongo believed that the center point and horizontal line held multiple denotations: it was a sacred space upon which an individual could swear to God and the ancestors; it divided the land of the living from the dead; and summarized the wholeness of an individual who possessed knowledge of both realms. The intersections of the cross—“the fork in the road,” “turn in the path,” or crossroads were but a passage in the progression of change (1983, 109). God, maleness, high noon, and earthly strength are signified by the northern point of the cruciform. Ancestors and the strength of the underworld, femaleness, and midnight are symbolized by the cosmogram’s southern point. The horizontal demarcation between north and south was the water way or Kalunga line which could be marked by a body of water or dense forestation. Positioned to the east was dawn or the beginning of one’s life, and to the west, dusk or death. According to Thompson, “[O]ne of the major functions of the cosmogram of Kongo [was] to validate a space on which to stand a person” (110). Lydia Cabrera in her 1954 text, El Monte: Igbo Fina Ewe Orisha, Vititinfida, affirms the convergence of the cosmogram’s intersecting roads as the place where one can find grounding, stating, “All spirits seat themselves on the center of the sign as the source of firmness” (qtd. in Thompson 110). Within the tradition of the African diasporic canon, the crossroads is denoted as the site of contemplation, alternatives, and transition. It is the locale to which one returns to consider, as cautioned in the popular 1995 song, “Tha Crossroads,” “[W]hat’cha gonna do, when there ain’t nowhere to run, when judgment comes for you” (Bone Thugs-n-Harmony 1995).

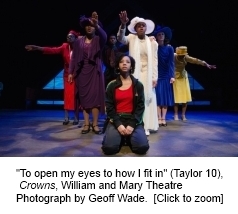

In Crowns, the ideology of the Kongo Cosmogram is materialized in Yolanda’s crossing of the Mason-Dixon line, a crossing that suggests not only a physical but, a metaphysical journey. Likewise,the death of her brother Teddy, the play’s inciting incident, is the ordeal that metaphorically situates Yolanda at the crossroads of reflection and consideration. In her dis-eased state, her mother initiates Yolanda’s journey of the self:

After his funeral

Ma sent me away

Down South

To open the door

To let the light in

On a brand-new day

To Grandma’s house

To consider my sins

To open my eyes to how I fit in—

To open my eyes to how I fit in— (Taylor 10)

Situating the play in Darlington, SC, approximately an hour and a half from the Atlantic Ocean coastline allows Taylor to tap into the cultural software of the land. The Trans-Atlantic slave trade with its trafficking of bodies steeped with their own “cultural intelligence” (Irobi 2009, 17), contributed to the fashioning of an African American identity in the 17th century and certainly into the present. In 1970 Oba Efuntola Oseijeman Adelabu Adefunmi I further added to the African-based ritual culture of South Carolina with the construction of Oyotunji African Village in Beaufort, thus creating a literal material site of the African presence in America. The village’s website describes it as the “first intentional community based on the culture of the Yoruba and Dahomey Tribes of West Africa” (Oyotunji Village 2015).

Situating the play in Darlington, SC, approximately an hour and a half from the Atlantic Ocean coastline allows Taylor to tap into the cultural software of the land. The Trans-Atlantic slave trade with its trafficking of bodies steeped with their own “cultural intelligence” (Irobi 2009, 17), contributed to the fashioning of an African American identity in the 17th century and certainly into the present. In 1970 Oba Efuntola Oseijeman Adelabu Adefunmi I further added to the African-based ritual culture of South Carolina with the construction of Oyotunji African Village in Beaufort, thus creating a literal material site of the African presence in America. The village’s website describes it as the “first intentional community based on the culture of the Yoruba and Dahomey Tribes of West Africa” (Oyotunji Village 2015).

When Yolanda crosses the Kalunga line (i.e., the Mason-Dixon line), she meets a community of spiritual energies (personified here as Yoruba Orishas)—mediation and choice (Elẹ́gbá), wisdom (Ọbàtálá), will (Ṣàngό), change (Ọya), reflection (Ọ̀ṣun), and regeneration (Yemọja)—who facilitate her search for self-harmony and demonstrate how her life is intricately tied to a larger spiritual matrix and physical community. Clearly, aesthetic elements of the Orisha tradition within Yoruba culture shape the play’s characterizations as Taylor reduces the over fifty women documented in Cunningham and Marberry’s original book down to seven divine “energies that manifest in nature and within human life” (Ford 1999, 145):

Mother Shaw / Obatala: Orisha of wisdom, creativity

Mabel / Shango: Orisha of fire (red and white)

Velma / Oya: Orisha of storms (purple)

Wanda/ Oshun: Orisha of the rivers and water (gold and yellow)

Jeanette/ Yemaya: Orisha of seas (blue)

Yolanda/ Ogun: (green and red) [3]

Man/ Elegba: Orisha of crossroads (red and black) (Taylor 7)

According to Baba Ifa Karade’s The Handbook of Yoruba Religious Concepts, the word Orisha is a pairing of two Yoruba words, Orí – head or human consciousness, and sha – divine consciousness. Thus, the Orisha epitomize “human divinity potential” (1994, 23) and serve as accessible examples of individuals with emulative character traits, that if integrated, will assist Yolanda in developing a well-balanced personality. Known in the New World as the Seven African Powers, the collective of forces work on Yolanda’s behalf to help “bring [her] into accord with the eternal mysteries of being, to help [her] manage the inevitable passages of [her life]. . .and to help her [reestablish] harmony in the wake of chaos” (Ford 1999, viii; ix). With the guidance of these spiritual and ancestral forces, Yolanda establishes a connection “to the Motherland. . .[herself]. . .and all ancestors who’ve crossed over” (Taylor 43). In this article, I will confine the analysis to the three most important characters (and their corresponding Orisha), Man/Elẹ́gbá, Mother Shaw/Ọbàtálá, and Yolanda/Ògún.

Man/ Elẹ́gbá

In the Orisha tradition, Elẹ́gbá is the messenger between humanity and the divine, and the owner of crossroads, meaning all thresholds of choice and change (including doors, roads and states of consciousness). His duality, demonstrated through his colors of red and black, personifies his intersectionality with orún (the invisible realm) and aiye (the physical realm). In the human body, which some scholars have theorized as a mirror of the cosmos, Elẹ́gbá resides at the base of the neck, along the spine, mediating between the head or orún and the body or aiye. Thus, in Crowns, in his mediatory role Man/Elẹ́gbá’s goal is to facilitate communication and balance between Yolanda’s dual selves—her inner head (Orí-inù) and her celestial head (Orí-ìpònrì). A trickster figure, as indicated by his orature, Elẹ́gbá performs the roles of multiple characters within the text—fathers, husbands, as well as Yolanda’s older brother Teddy.

In the prologue the stage directions read as follows: “We hear African music as lights come up on Man. He strikes his staff on the floor three times and lights come up on Yolanda, who stands on the lip of the stage” (Taylor 9). These directions reference his aesthetics. The number 3, as well as 7, and 21, are Elẹ́gbá’s ceremonial numbers; his garabato (staff), according to Yoruba authority Orimolade Ogunjimi (with whom I worked while directing Crowns for William and Mary Theatre), is an instrument of ritual used for reaching, hooking, pulling, drawing things together or guiding.[4] In this instance Man/Elẹ́gbá’s garabato does several things:

1. Striking it on the floor three times initiates light. Sound erupting into light suggests the making of a creation story as evidenced in Genesis 1:3, which states, “And God said, ‘Let there be light: and there was light.’” Considering light as awareness or consciousness, Man in his dual role as preacher and mediating spiritual force not only brings our attention to Yolanda and affirms his role as ritual officiant but, also initiates the opening of Yolanda’s consciousness.

2. With his garabato, Man/Elẹ́gbá opens the way for the descent of additional spiritual forces. This ritual signification is accompanied by the refrain, “Eshe o baba eshe” to which the women respond, “Eshe o baba” (Taylor 10). The tributary phrase is a condensed version of the mojubar or prayer and libation given before sacred or social gatherings. The mojubar is offered in reverence of the Creator, Orisha, ancestors, and spiritual leaders as well as to implore protection from death, sickness, loss, and tragedy.

3. The women gather and begin to sing an ọfọ̀ or incantation described as “a traditional spiritual about rising. . . [becoming] more complex traveling through different times—field hollers—over the ocean—to Africa and forward again layering in jazz-blues” (Taylor 10). The incantation includes multiple expressions of àṣẹ (the power to make things happen)—sounds and vibrations, references to Gullah language—intended to wake up the gods, spiritually charge the atmosphere, and situate Africa as the point of origin for the retentions evident in the music in Crowns—“field hollers. . . spirituals. . . blues, jazz. . .gospel. . .and contemporary hip-hop” music (Palmer 2012, 8).

Mother Shaw/ Ọbàtálá

Mother Shaw’s Orisha archetype is Ọbàtálá, head of the Orisha, the Orisha of wisdom, and molder of human beings, most particularly the head. As such Ọbàtálá holds dominion over creation and human consciousness. As Yolanda’s grandmother and spiritual mother, Mother Shaw helps to reshape Yolanda’s consciousness and facilitates the peace and lucidity that Ọbàtálá is known to provide during times of trouble and confusion. Known alternatively as “King of the White Cloth or Light,” these associations speak of Ọbàtálá’s perceptiveness and ability to keep all things in perspective. Taylor underscores Ọbàtálá’s acuity in the stories Mother Shaw tells about her mother who went blind from glaucoma at the age of twenty-six. Without sight, she gave birth to five children, taught them to read by the way they described the letters, and slapped the hands of those who believed they were absconding with biscuits unbeknownst to her. The community regards Mother Shaw as “stately. . .graceful,” and bestowed upon her the moniker of “National Prayer Warrior” for her ability to usher in the spirit. She keeps the peace between the other competitive Hat Queens and reminds them that their goal is to be patient, long-suffering, uncomplaining, and harmonious “just like Jesus” (Taylor 23). . . and Ọbàtálá.

Mother Shaw’s Orisha archetype is Ọbàtálá, head of the Orisha, the Orisha of wisdom, and molder of human beings, most particularly the head. As such Ọbàtálá holds dominion over creation and human consciousness. As Yolanda’s grandmother and spiritual mother, Mother Shaw helps to reshape Yolanda’s consciousness and facilitates the peace and lucidity that Ọbàtálá is known to provide during times of trouble and confusion. Known alternatively as “King of the White Cloth or Light,” these associations speak of Ọbàtálá’s perceptiveness and ability to keep all things in perspective. Taylor underscores Ọbàtálá’s acuity in the stories Mother Shaw tells about her mother who went blind from glaucoma at the age of twenty-six. Without sight, she gave birth to five children, taught them to read by the way they described the letters, and slapped the hands of those who believed they were absconding with biscuits unbeknownst to her. The community regards Mother Shaw as “stately. . .graceful,” and bestowed upon her the moniker of “National Prayer Warrior” for her ability to usher in the spirit. She keeps the peace between the other competitive Hat Queens and reminds them that their goal is to be patient, long-suffering, uncomplaining, and harmonious “just like Jesus” (Taylor 23). . . and Ọbàtálá.

Mother Shaw’s opening song is a strong signpost of her association with Ọbàtálá and cryptically dramatizes Yoruba metaphysical and theoretical ideas of the self. In the opening, “Mother Shaw’s Song” reminds Yolanda:

I got a crown up in that Kingdom

Ain’t that good news (Taylor 13).

The spiritual dramatizes Ọbàtálá’s tolerant disposition and assurance about life in the afterlife despite earthly suffering, as well as echoes the Yoruba concept of the Orí, one’s inner head, personal destiny, or divine consciousness. In “Crowning Achievements,” Mary Jo Arnoldi and Christine Kreamer (1995, 23–24) write:

Among the Yoruba in Nigeria. . .the head is the seat of ori, personal destiny. Surrounding this “inner head,” the physical head, visible to the world, becomes the focus of many important rituals…. Among the Kaguru of Tanzania, the top of the head should be respected; one should avoid touching others in this spot. The head connects persons to birth and ultimately to the land of the dead (Beidelman 1993: 64). Among the Kalabari Ijo of southeast Nigeria, the head, specifically the forehead is the locus of the spirit, teme, that control’s one’s behavior (Barley 1988: 16).

So what is the crown that remains in the kingdom of which Mother Shaw/Ọbàtáláspeaks? According to Awo Fá’lokun Fatunmbi in Ìbà’se Òrìsà, the total self (Tikara-eni) is composed of five elements: (1) Ara, the physical self (flesh, bone, heart, intestines) (2) Ègbè, the emotional self (heart) (3) Orí, the physical head or conscious self (forehead, crown, back of skull) (4) Orí-ìnu, the inner self (character, personal destiny) and (5) Orí-ìpònrì,the higher self (1994, 69–82). It is one’s crown, the top of one’s head, which links to one’s higher self (Orí-ìpònrì).

The higher self is one’s transcendent, primal or perfect double in the invisible realm. With the permission of the creator, the Orí journey to earth but, upon descending through the symbolic metaphysical spaces of the water within a mother’s womb, the Odo-Aro (blue river or river of dye) and of the birth canal, the Odo-Eje (blood river), the Orí-ìnu and Orí-ìpònrì separate, with the Orí-ìpònrì remaining in heaven (Fatunmbi 1992, 97). As an infant is detached from its mother’s umbilical cord upon birth, there is a rupture between the two levels of consciousness. Without spiritual guidance, as one encounters life’s vicissitudes, the Orí-ìpònrì becomes more difficult to engage, leaving one as a wandering Everyman, disharmonious, and morally bereft. Thus, Mother Shaw is concerned with both the cultural and spiritual development of Yolanda’s consciousness, and desires to reawaken the elevated, heavenly aspect of Yolanda’s fragmented self. Her testimonies serve to remind Yolanda of her existing internal light and divine preeminence.

Yolanda/ Ògún

Though she is the play’s heroine (the text is constructed around her), Yolanda’s character profile is scant. We know that she is the youngest of five children. She had planned to attend college as did her older brother but, she became sidetracked after he left for school. He eventually dropped out of college and followed her into the streets. Might this choice have had something to do with his murder? It is clear that she feels some guilt surrounding her brother’s death. Her mother is employed in the service sector; there is no mention of a father. She alludes to her solo status in a male-dominated gang. Yolanda is also the only character listed in the play without any Orisha attributes besides the colors green and red of her Orisha counterpart, Ògún. My reading of this omission suggests a crisis of identity, cultural rootlessness, or the loss of an essence ideal. There is a sense of individual determinism and marginalization that becomes apparent in her statements such as “hats are like my own thing” (Taylor 17), or “I don’t know how to be one of them” (25), after pulling “away outside the circle”of the ring shout (24). While her sense of individuality is not wholly problematic, the statements reflect her lack of cultural awareness and psychological fragmentation.

Yolanda’s patron spirit, Ògún, is the “god of iron,” and is associated with hunting, warfare, industrialization, and technology. From these connotations one can see his dual nature as a creator and destroyer. Sandra T. Barnes in Africa’s Ogun describes him as a deity of “many faces. . .both violent and the ideal male: nurturing, protective, and relentless in his pursuit of truth, equity and justice” (1989, 2). She states further that in his twin-fold nature lies “the human dilemma” to maintain harmony between “control/lack of control, sacrality/violence, protection/destruction” (19). Implements related to his cultivating and transformative abilities include the machete (clearing), knife (carving), anvil (transforming), railroad spikes/nails/pick (binding, piercing), hammer (bending), rake (smoothing), hoe (cutting), and pry (uprooting). Ògún’s implements and transformative energy are used best when removing or destroying the obstacles (internal or external) that would hinder one’s spiritual growth. But, what happens when only the destructive side of his nature is displayed? Or when his warrior energy is misplaced?

Yolanda’s alienation, both mental and social, at home and in her new environment, bespeaks of the lore of Ògún. In Fatunmbi’s Ogun, Ifá and the Spirit of Iron, orature such as “Ògún Adé” and “Ògún Wa’le Onire,” demonstrates Ògún’s cycle of disparagement or external rejection followed by acts of destruction and his subsequent self-imposed exile or isolation period. In the story of “Ògún Adé,” he travels to meet friends in Ile Ife. On the way, he assists a neighboring village in defending their enemies. He arrives in Ile Ife tired, ragged and covered in blood. Unrecognized, he is asked to leave. He returns after cleaning up and the community, ashamed, asks him to stay. Still hurt from the initial rejection, he refuses and retreats to the forest (Fatunmbi 1994, 4). The wild man perception of Ògún by his community leads in part to his social isolation. Yolanda, with her self-described unique style, has a similar experience. In her rap, she states:

From high school

Created my own way of clothes

Matching gangster brim,

Cap—or a derby on (Taylor 9).

Yolanda expresses Ògún’s creative energy through her dress. Her clothing is the means by which she expresses her individuality and power but, through her own admission, her style intends to induce shock and communicate nothing about her identity (29). Perhaps her panache, (which may have formerly won her admiration from her Brooklyn peers), coupled with her anti-social behavior, is a “rebel dance” (25), the formation of an alternative language which would render her visible and hence seen in a world in which she feels largely invisible. However, her peers in Darlington responded to her creativity with taunts such as “Voodoo woman,” “Witch,” and “Stupid” (29), derision she endured for an entire year before a passionate outburst:

One day, I wore my brother’s red cap—with the bill to the side—I was blazin.’ I walked right up to them and stuck my finger in their faces. I said, “You tried to make me change but I’m still me. I’ve had worse than this trifling teasing and I’m not going to crack.” They backed off after that (29).

Sharing Ògún’s tendency to stifle emotions, Yolanda’s reaction affirms what Phillip Neimark writes in The Way of the Orisa; “The children of Ogun must not repress” (1993, 86), lest they explode in inappropriate ways.

The geographical contexts to which Yolanda pledges allegiance, Brooklyn and Englewood, also offer additional insight into what cannot be gleaned about her background from the text. In 2012 during the 10th anniversary production of Crowns at the Goodman Theatre, Taylor, who had recently relocated to Chicago, turned up the lamp on the play’s social concerns—a thematic consideration of importance but, secondary to the play’s predominant focus on why Black women crowned their heads. That particular year, Chicago suffered from a high rate of homicides (503), 68 more than in 2011 (Christensen 2015). In an interview with Rolling Out, Taylor says that she “moved to Chicago to find unification of place.” She wished to use Crowns “to connect with the current issues of Chicago communities . . . to address the gang violence which shatters families. Thus, as “Yolanda’s Rap” indicates below “[she] is now a 17 year old from Englewood” (Admin 2012a):

I’m from Englewood homey hanging with boys

Commanding respect don’t take no noise

It was a lot of fun being buck wild

Running the streets and doing it in style (WTTW Chicago 2012).

While these lines from her rap provide insight into her characterization, we also begin to form a certain perception of the Englewood community. For the period of 2008–2012, the Data Portal for the City of Chicago reports a per capita income of $11,888, a poverty rate of 46.6 percent, a crowded housing rate of 3.8 percent, and a youth unemployment rate of 28 percent. Of Englewood residents aged 25 or under, 28.5 percent had no high school diploma (City of Chicago Data Portal 2015).

Comparatively, Brooklyn, which is reported to be thefourth largest city in America, fared no better according to 2012 statistics. In Brownsville, one of Brooklyn’s poorest residential communities, sixty-nine people were shot in 2012 alone (Milin and Croghan 2012). According to statistics provided by the Brooklyn Community Foundation’s webpage: Brooklyn has nearly one in four people living in poverty (more than Detroit) and has the most units of public housing in New York City; Brownsville alone has the highest concentration of public housing in the nation. Over 30 percent of renters spend more than half of their income on rent; 3,319 Brooklyn families entered New York City homeless shelters in 2011. One in five residents over the age of twenty-five [do] not have a high school diploma. In addition, three thousand Brooklyn residents a year are admitted to prison at a projected cost of over $300 million.

This socioeconomic evidence of inequitable wealth distribution and failing educational infrastructures—coupled with urban renewal, ruthless policing without accountability, and criminalization of noncriminal behavior—highlights the fertile antecedents for the social disorder that breeds disoriented youth who, like Yolanda, are eroded of hope and seeming possibility.

In Crowns Taylor uses the concept of Ògún as a root metaphor to represent the rampant social decay within major urban American spaces, portending that the stress of systemic oppression can lead to spiritual fragmentation and cultural maiming within the people. Yolanda, as the embodiment of young Black urban America suffers from an Ògún Complex. Rather than utilizing the essence of Ògún in the service of transforming the systemic concerns from which she is internally grieving, the warrior energy is misplaced resulting in a “buck wild” and lawless “dead soul” (Taylor 9; 25). Such a complex results from emotional imbalance and psychological alienation from the regenerative aspect of one’s higher self. When methods of self-correction to restore balance are not imposed the Ògún Complex subsequently leads to acts of destruction (either to the self or extensions of the self, i.e. the community). Regenerative acts could include, but are not limited to, connecting with one’s higher consciousness, participating in acts that create or preserve life, or engaging in expressions of inventiveness.

Yolanda’s departure from her hometown was not self-imposed. Rather her mother orchestrated the intervention as a method of correction. However Yolanda discloses that she was “looking for answers – [l]ooking for [her]self” (Taylor 37); thus, it was a journey she knew was necessary. The “departure” as correction serves the same purpose as Ògún’s self-compulsory isolation—to engage in self-reflection so as to restore self-harmony (Barnes 1989, 18). With resolve and compassion, the community gathers with the intent to assist Yolanda in quelling her internal dis-ease by offering her spiritual and cultural wisdom and a listening ear. It is this demonstration of love that makes her “want to do right”— go to school, study Africa, and get in touch with her inner being (30; 43). Ultimately all of these efforts will work together in the formation of a new language (or technology) that can be directed in the service of Ògún’s greatest concerns—justice and the removal of obstructions that encumber discipline and spiritual development. With Crowns, Taylor demonstrates that extended family and intra-community support, intergenerational communication, and the recovery of spiritual and cultural understanding all serve as reformative acts to temper the spirit of iron when it turns in on itself in destructive ways.

The concept of an Ògún Complex is a “critical theory of spirit” and a useful framework for understanding present realities and discussing the underlying “spiritual conditions and spiritual activity” (Rahming 2013, 37). Such an alternative language applied to the recent uprising in Baltimore, for example, draws attention to the core issues and provides a critical language for framing and discussing the root causes of external social discord. With a focus on the spiritual energy, there is always the hope of regeneration.

Gullah Culture as Structural Design

In addition to Yoruba aesthetic and theoretical considerations, a second geographical influence is evidenced through Taylor’s appropriation of ritual associated with Gullah creole culture. The structural outline for Yolanda’s search for self bears indices of the Gullah Seeking Ritual. In “Gullah Attitudes toward Life and Death,” religious historian Margaret Washington Creel regards the seeking ritual as the “spiritual metamorphosis, symbolic death and rebirth” of an individual who desires to “catch sense” or seek membership into a praise house or plantation sphere. The seeking journey begins "with a personal decision not devoid of community pressure," followed by the seeker’s choosing of a spiritual godparent, which is usually made clear to them by way of a dream. This spiritual parent will instruct them on proper spiritual deportment. In lieu of social contact, the seeker departs from the community and goes into ‘de wilderness’ for prayer, solitude, and meditation.” This stage of isolation and reflection is known as “de trabbel [travel] period.” The seeker travels, experiencing “warnings, awful sights or sounds,” and envisions being led to the river by a “white man.” The travel period concludes at the discretion of the spiritual parent with assessment by the spiritual community, followed by baptism and a formal presentation of the new member to the Praise House. “Following baptism and church fellowship, new members engage in a ring shout” (2005, 164–165). Thus, the stages of the Gullah Seeking Ritual are: decision with pressure from outside influences, selection of spiritual godparent, isolation and reflection (travel period), evaluation, purification through baptism, presentation to the community, and celebration through ring shout.

In the tradition of many northern African American families who wish to maintain cultural ties, Yolanda, who insists several times throughout the play that Brooklyn is where she belongs, is sent south for a period of introspection and conscious awakening. The decision is made by Yolanda’s mother who also selects the spiritual godparent, Mother Shaw. Although it is Yolanda’s mother who chooses the spiritual godparent and not Yolanda herself and the selection is not made by way of a literal dream, the parallel with the Seeking Ritual still remains. In Psychology Today, Dr. Robert Berezin writes that “[t]he work of dreaming is to digest and detoxify conflict stirred during the previous day and recent past (2015). Yolanda is sent to Mother Shaw to help her “digest and detoxify [the internal] conflict” she is experiencing. Thus, the function of dreaming and the goal of Yolanda’s mother are one in the same. Upon her arrival in Darlington she begins “de trabbel period” (travel period), the stage of isolation and reflection. She remains there for much of the play.

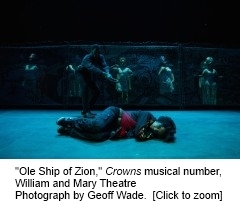

During the evaluation period, the community is able to assess the effect of their epistemic testimonies on Yolanda. In the funeral sequence after the community discloses individual stories of the loss, “[a]ll look at Yolanda expectantly” (Taylor 36). With difficulty (because children of Ògún have difficulty expressing their emotions) but, an open heart and vulnerability, she discusses the details of her brother’s death. In her discourse she admits to the guilt she feels about her brother. He followed her “down a rough road” (37). After Mother Shaw’s narration about decorous resistance in the face of oppression, she extends her arms to her granddaughter who accepts the invitation to baptism by stepping forward. Mother Shaw leads “Ole Ship of Zion” and “Take Me to the Water,” which conjure up images of crossings and encourage Yolanda to remain steadfast and courageous in her decision to reconnect with her higher consciousness (Orí-ìpònrì). During the purification rite, which reads similarly as an Ògún wíwè (washing of Ògún), old dispositions are washed away. Reborn, she is tempered and fortified against negative forces, and the hope is that her future behavior will reflect her essence ideal. The metaphysical crossing of water reconnects her with memories of an “ancient body”—her mother, Africa:

And her voice

Became a river of voices

Washing over me

Swept up by tidewater

Taking me under

I can’t breath

I am rolling—rocked

By some ancient body

Remembering Ma

Rocking me as a baby

And feeling other hands

Laying hands upon me

Holding, caressing,

Lifting me.

Not like some one

That want to be using me

And I give myself over

And I feel that I am losing me . . .

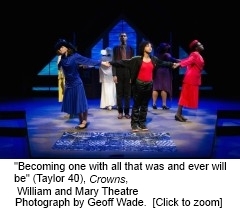

Becoming one with all

That was and will ever be (Taylor 40).

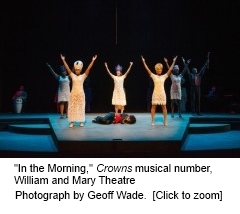

It is during the presentation stage, Yolanda, “simply – humbly – heartfelt – transformed,” stands before a rejoicing and welcoming community and sings about the joy she feels in her soul. She is embraced into the fold through song. At the play’s end, she understands her place within a larger tradition of African American history and her eyes are opened to how she fits within the community. In addition to her street hats, she embraces church hats and gelees as an act of spiritual and cultural communion (41). The final stage, the celebratory ring shout, is suggested in the circuitous structure of the play as it ends where it begins, with Mother Shaw’s references, through song, to her crown in heaven. Her testimony, which is embraced by the entire company at the end of the play, is an expression of faith and a reminder to each of them of their elevated divine status so as to inspire ideal social behaviors. While a literal ring shout is performed much earlier in the play (23–24), Yolanda was the missing element. Now that she has been initiated into the community she demonstrates her new status and understanding by participating in its rituals and customs.

Conclusion

In the introduction to Literary Expressions of African Spirituality, Carol P. Marsh-Lockett and Elizabeth J. West write of a Mende proverb that reads, “[T]o cry over your dead, you must go back to your mother tongue” (2013, 3). Taylor’s utilization of Yoruba ideological and aesthetic elements and Gullah religious traditions—a mother tongue immersed in a pre-Middle Passage dramaturgy—facilitates Yolanda’s somatic and supernatural quest to interrogate the past to make sense of her present and to reconstruct her spiritually fragmented self. Her sorrow, rage, fragmentation, and hopelessness send her to the symbolic womb of the South and she emerges from this motherland wiser and whole.

Notes

[1] . James Padilioni Jr., personal communication, March 11, 2015, via Facebook Messenger.

2. Michael Harris (untitled lecture on the shifting paradigm of African Diasporic aesthetics in visual arts, NEH Summer Institute on Black Aesthetics and African Centered Cultural Expressions: Sacred Systems in the Nexus between Cultural Studies, Religion and Philosophy, Hammonds House Museum, Atlanta, GA, July 17, 2014).

3. The cast of characters from the play script lists only colors for Ògún. I make reference to his attributes later in the article.

4. Orimolade Ogunjimi, personal communication, February 25, 2015 at Phi Beta Kappa Hall, College of William and Mary.

Works Cited

Admin. 2012a. “Regina Taylor Brings ‘Crowns’ to Chicago.” Rolling Out. June 26. http://rollingout.com/entertainment/regina-taylor-brings-crowns-to-chicago/(accessed April 10, 2015).

———. 2012b. “[Interview] Regina Taylor is Back on the Main Stage with ‘Crowns.’” Ebony. July 12. http://www.ebony.com/entertainment-culture/interview-regina-taylor-is-back-on-the-main-stage-with-crowns#.VTp4Dr7QfIU (accessed April 1, 2015).

Ademuleya, Babasehinde A. 2007. “The Concept of Ori in the Traditional Yoruba Visual Representation of Human Figures.” Nordic Journal of African Studies 16, no. 2: 212–220.

Arnoldi, Mary Jo and Christine Kreamer. 1995. “Crowning Achievements: African Arts of Dressing the Head.” African Arts 28, no. 1: 23–24. doi: 10.2307/3337248, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3337248 (accessed November 17, 2004).

Barley, Nigel. 1988. Foreheads of the Dead: An Anthropological View of Kalabari Ancestral Screens. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Barnes, Sandra T. 1989. “The Many Faces of Ogun: Introduction to the First Edition.” In Africa’s Ogun, edited by Sandra T. Barnes, 1–27. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Beidelman, Thomas.O. 1983. The Kaguru: A Matrilineal People of East Africa. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

Berezin, Robert. 2013. “Reflections on Dreaming and Consciousness.” Psychology Today, October 25. https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-theater-the-brain/201310/reflections-dreaming-and-consciousness (accessed April 24, 2015).

Bone Thugs-n-Harmony. 1995. “Tha Crossroads.” In E. 1999 Eternal. Compton: Ruthless Recordings.

City of Chicago Data Portal. “Selected Socioeconomic Indicators in Chicago, 2008–2012.” https://data.cityofchicago.org/Health-Human-Services/Census-Data-Selected-socioeconomic-indicators-in-C/kn9c-c2s2(accessed March 24, 2015).

Christensen, Jen. 2014. “Tackling Chicago’s ‘Crime Gap.’” CNN. March 14. http://www.cnn.com/2014/03/13/us/chicago-crime-gap/ (accessed April 19, 2015).

Creel, Mary Washington. 2005. “Gullah Attitudes toward Life and Death.” In Africanisms in American Culture, 2nd ed., edited by Joseph E. Holloway, 152–186. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Cunningham, Michael and Craig Marberry. 2000. Crowns: Portraits of Black Women in Church Hats. New York: Doubleday.

Fatunmbi, Awo Fá’lokun. 1992. Awo: Ifá and the Theology of Orisha Divination. Plainview: Original Publications.

_____. 1994. Ìbà’se Òrìsà: Ifa Proverbs, Folktales, Sacred History, and Prayer.Bronx, New York: Original Publications.

Ford, Clyde. 1999. The Hero with an African Face. New York: Bantam Books.

Foucault, Michel. 1988. Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault, edited by L.H. Martin, H. Gurtman and P.H. Hutton. London: Tavistock.

Harrison, Paul Carter. 1974. Kuntu Drama: Plays of the African Continuum. New York: Grove Press.

Irobi, Esiaba. 2009. “The Theory of Ase: the Persistence of African Performance Aesthetics in North American Diaspora—August Wilson, Ntozake Shange & Djanet Sears,” in African Theatre 8: Diasporas, edited by Christine Matzke and Osita Okagbue, 15–25. Rochester: James Currey.

Karade, Baba Ifa. 1994. The Handbook of Yoruba Religious Concepts. York Beach, ME: Red Wheel/Weiser.

Love, Velma E. 2012. Divining the Self: A Study in Yoruba Myth and Human Consciousness. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Marsh-Lockett, Carol P. and Elizabeth J. West. 2013. Literary Expressions of African Spirituality. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Milin, Elena and Lore Croghan. 2012. “Tale of Two Worlds: Statistics Paint Picture of Extremes of Wealth and Poverty that Exist Side by Side in Brooklyn.” NY Daily News, August 22. http://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/brooklyn/tale-worlds-statistics-paint-picture-extremes-wealth-poverty-exist-side-side-brooklyn-article-1.1142487(accessed March 26, 2015).

Neimark, Philip, John. 1993. The Way of the Orisa, Empowering Your Life Through the Ancient African Religion of Ifa. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Oyotunji African Village. “About Oyotunji African Village.” http://www.oyotunji.org/about-oav.html (accessed February 1, 2015).

Palmer, Tanya. 2012. “Crowns Revisited: An Interview with Regina Taylor.” OnStage 27, no. 5: 2–4. http://www.goodmantheatre.org/Documents/OnStage/1112/Crowns_OnStage.pdf

(accessed March 15, 2015).

Plate, Liedeke and Anneke Smelik. 2013. Performing Memory in Art and Popular Culture. New York: Routledge.

Rahming, Melvin B. 2013. “Reading Spirit: Cosmological Considerations in Garfield Linton’s Vodoomation: A Book of Foretelling.” In Literary Expressions of African Spirituality, edited by Carol P. Marsh-Lockett and Elizabeth J. West, 35–62. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Taylor, Regina. 2005. Crowns. New York: Dramatists Play Service.

Thompson, Robert F. 1983. Flash of the Spirit: African & Afro-American Art & Philosophy.New York: Random House.

WTTW Chicago. 2012. “‘Yolanda’s Rap’ from Crowns at Chicago’s Goodman Theatre.” YouTube video, 1:29. July 5. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hNB77BMDiD8(accessed 17 July 2015).

Artisia Green is an associate professor of Theatre and Africana Studies at the College of William and Mary. A director and dramaturge, Artisia’s current research is in decoding traditional African systems of thought in creative expression with a particular interest in Yorùbá philosophical systems. She attended the 2014 National Endowment for the Humanities Institute, “Black Aesthetics and African Centered Cultural Expressions: Sacred Systems in the Nexus between Cultural Studies, Religion and Philosophy, where she further developed her research on spiritual expression in Black dramatic literature