(The play was Rachel by Angelina Weld Grimké)

KC MeltingPot Theatre, The Keairnes Stage at Just Off Broadway Theatre, Kansas City, Missouri

19 November 2016

By Cheryl Black

In 1909, the NAACP launched a national crusade against lynching, the most violent and heinous of extra-legal but socially sanctioned manifestations of white supremacy. In 1916 black scholar William Pickens asserted that “disclosures of southern brutalities would be an essential precondition to ending mob violence.”[1] That same year Washington D.C. teacher, poet, and playwright Angelina Weld Grimké answered that call, offering Rachel (original title Blessed Are the Barren), a play that dramatized a young black woman’s brutal awakening to racial violence, an awakening that forces her to renounce marriage and motherhood rather than to bring children into a world bent on their destruction. A century since its premiere, the play resonates powerfully in the present day, as a latter-day “anti-lynching’’ crusade, The Black Lives Matter movement, has emerged to combat racism and racist violence and to celebrate and honor black experience.

Nicole Hodges Persley’s sensitive staging of Grimké’s play, though scrupulously faithful to Grimké’s text, allows the present to filter through. Written in a style consistent with the well-made realist dramas of her era, Grimké’s text includes detailed, scene-setting descriptions of the plants, books, paintings, window dressings, dishes, rugs, and other properties that furnish the Loving family home where young Rachel Loving lives with her widowed mother and brother Tom. However, the thrust configuration of the Keairnes Stage and Warren Deckert’s selectively realist design unmoor the play from its early 20th century aesthetic tradition. Although the pieces onstage appear authentically late Victorian, the very openness of the space–the absence of the walls and doors of box sets that contain both action and audience imagination–intrudes on this image of a bygone era. In this visual context, the few strategically placed decorative properties gain added significance – a mantle clock upstage center reminds us of time. Directly above it, a mirror in a gilded frame facing front invites the audience to see themselves in this universe. Karen Cushenberry’s costumes are similarly vintage. Yet her choice to dress all the characters in shades of white serves to abstract and universalize the effect.

Nicole Hodges Persley’s sensitive staging of Grimké’s play, though scrupulously faithful to Grimké’s text, allows the present to filter through. Written in a style consistent with the well-made realist dramas of her era, Grimké’s text includes detailed, scene-setting descriptions of the plants, books, paintings, window dressings, dishes, rugs, and other properties that furnish the Loving family home where young Rachel Loving lives with her widowed mother and brother Tom. However, the thrust configuration of the Keairnes Stage and Warren Deckert’s selectively realist design unmoor the play from its early 20th century aesthetic tradition. Although the pieces onstage appear authentically late Victorian, the very openness of the space–the absence of the walls and doors of box sets that contain both action and audience imagination–intrudes on this image of a bygone era. In this visual context, the few strategically placed decorative properties gain added significance – a mantle clock upstage center reminds us of time. Directly above it, a mirror in a gilded frame facing front invites the audience to see themselves in this universe. Karen Cushenberry’s costumes are similarly vintage. Yet her choice to dress all the characters in shades of white serves to abstract and universalize the effect.

Evocative pre-show and intermission music (sound design by Persley and Laura Burt) similarly bridge eras, in Persley’s words, allowing audiences to “travel sonically through African American music that chronicles [past and present] trauma.” Selections range from Scott Joplin’s “Heliotrope Bouquet” and the Fisk Jubilee Singers’ “Oh Freedom” to Duke Ellington’s “Weary Blues,” Mary Lou Williams’ rendition of Billie Holliday’s “Motherless Child,” Tracy Chapman’s “I’ll Never Love,” and Alicia Keys’ 2016 version of the 19th century spiritual “Deep River.”

Grimké’s dialogue is challenging for a 21st century performer. A work spanning years in time but restricted to one interior location requires considerable exposition; every adult character has several lengthy monologues. The gut-wrenching emotional demands are equally extraordinary as Mrs. Loving re-lives the night her husband and first-born son were lynched by a white mob, as Tom Loving and John Strong (a love interest for Rachel) express the frustration of denied economic opportunity, and as a prospective new neighbor, Mrs. Lane, shares with Rachel the story of her dark-skinned daughter’s daily humiliations. Rachel’s emotions reach fever-pitch as she discovers, first, the truth about her father, and is later forced to confront racist violence against two children, including her beloved adopted son (a young neighbor whose parents died of smallpox). Rachel rails against God for his cruelty and begs for understanding from her rejected lover. She ends each of the first two acts in a physical collapse. That Persley’s production succeeds as a deeply compelling evening of theatre is a testament to her and her cast, and perhaps also to the ultimate truths inherent and still resonant in Grimké’s play.

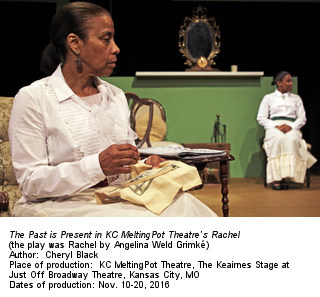

As Rachel, Shawna Downing is superbly cast, perfectly embodying the paragon of youthful joy and innocence created by Grimké and delineating Rachel’s transformation from innocence to despair with heartbreaking honesty. Lynn King, as Mrs. Loving, is the image of mature beauty and hard-won dignity. Despite the pain lurking in her eyes, King kept her physical and emotional life in check. Her spine never touched the back of a chair in which she sat. Persley staged Mrs. Loving’s agonizing disclosure of the lynching of her husband and son with King facing out, avoiding eye contact with Rachel and Tom, as if that was the only way she could tell that story without breaking down. This staging choice also gives the critical scene even more importance, one that resonates powerfully with a 21st century American audience.

As Rachel, Shawna Downing is superbly cast, perfectly embodying the paragon of youthful joy and innocence created by Grimké and delineating Rachel’s transformation from innocence to despair with heartbreaking honesty. Lynn King, as Mrs. Loving, is the image of mature beauty and hard-won dignity. Despite the pain lurking in her eyes, King kept her physical and emotional life in check. Her spine never touched the back of a chair in which she sat. Persley staged Mrs. Loving’s agonizing disclosure of the lynching of her husband and son with King facing out, avoiding eye contact with Rachel and Tom, as if that was the only way she could tell that story without breaking down. This staging choice also gives the critical scene even more importance, one that resonates powerfully with a 21st century American audience.

Although Mrs. Loving loses her husband and son to a lynch mob, Grimké highlights Mrs. Loving’s motherhood, evoking the appearance of the mothers of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and Tamir Rice on CNN in December 2014, and the current “Mothers of Black Sons” movement. Rachel’s response to this tale of horror focuses entirely on the “hundreds of dark mothers who live in fear, terrible, suffocating fear, whose rest by night is broken, and whose joy by day in their babies on their hearts is three parts–pain.” In November 2016, MeltingPot’s audience was only too aware of the contemporary relevance of that speech.

Lewis Morrow brought humor, intelligence, and a palpably smoldering resentment to Tom Loving. Sam Salary conveyed the requisite steadfast love and sorrowful comprehension in his portrayal of John Strong. Grimké introduces a complex and disturbing layer of racism exacerbated by class and gender during a scene between Rachel and Mrs. Lane. Mrs. Lane describes her family as “poor, ugly, and black,” in apparent contrast to Rachel who represents a more genteel and “brown” identity. Mrs. Lane’s daughter Ethel has been treated so cruelly in her previous school that the child is a nervous wreck, barely able to speak to anyone other than her mother. As Mrs. Lane, Aishah Ogbeh’s wry delivery introduced a surprisingly comic tone to this scene, with several lines evoking chuckles from the audience. The major impact of that scene, however, came from the little girl, Ethel, played by Haley James, sitting absolutely motionless and silent on the piano stool. Her tentative acceptance of a dish of apple slices, her painstakingly slow consumption of a single slice, as if she could not quite trust even so trivial a gift, was profoundly moving.

Grimké’s resolution was controversial in its day. She was accused of encouraging race suicide, and the play faded into obscurity after only a few productions. If anything, Persley’s staging, and Downing’s performance during the play’s final moments, add an ominous note of ambiguity to the play’s conclusion. Seeing Rachel’s breakdown, hearing her impassioned rejection of a future with John and her bitter denunciation of a cruelly laughing God as her traumatized adopted son weeps offstage, makes one wonder what in fact might happen after the lights go out.

Persley’s brilliantly staged curtain call is both reassuring and a perfect culmination of the evening as her cast bounds onstage as their 21st century selves, with looks that strikingly integrate the past and present–a wig removed, a baseball cap or sweatshirt added. Whatever Grimké intended, the message here seems clear: this play is a testament to a past history that has never been fully disclosed, a present still tragically affected by it, and a future reliant on our determination to acknowledge, confront, combat, and finally, relegate to the past racism and white supremacy in America.

Cheryl BlackUniversity of Missou

[1] Robert L. Zangrando, The NAACP Crusade Against Lynching, 1909-1950 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1980), 11.