Intersectionality in the Dramas of Mary Burrill, Alice Childress, and Pearl Cleage

By David B. Smith

“GRACIE: How many times in your life do you think you get to defy convention, challenge authority…?”

- Pearl Cleage, The Nacirema Society Requests… (77)

In 1919, African American educator and playwright Mary P. Burrill wrote They That Sit in Darkness, a one-act drama about the death of a poor black mother of seven. Half a century later, African American dramatist Alice Childress crafted Wine in the Wilderness, a 1969 play chronicling an artist who hopes to paint a lower-class, uncultured black woman amidst a night of rioting in Harlem. Finally, in 2013, African American playwright Pearl Cleage published The Nacirema Society Requests the Honor of Your Presence at a Celebration of Their First One Hundred Years, a comedic look at an upper-crust African American family set in Montgomery, Alabama in 1964. Each of these plays employs a similar dramatic style but are remarkably different in terms of their depictions of African Americans and their position within society. Nonetheless, this comparative analysis will contend that each playwright uses her drama to challenge cultural representations of African American women by emphasizing the real-life intersectional oppression that black women face.

For the purpose of this paper, it is necessary to develop a working definition of intersectional oppression. In their text Framing Intersectionality, feminist scholars Helma Lutz, Maria Vivar, and Linda Supik note that intersectional analysis focuses on the “interlocking of and interactions between different social structures” (2). In the context of this analysis, such structures include the historical subjugation of African Americans, systems of gendered discrimination, and poverty. The intersectional approach to the oppression of black women asserts that blackness and womanhood cannot be treated independently. In other words, the systems of oppression of African Americans and discrimination against women interact with and amplify one another within the lives and identities of black women. Thus, this analysis will argue that each play in question features black women who exist in the nexus of complex systems of racial, class, and gendered discrimination.

Two additional points of clarification are worth noting. Firstly, I contend that each playwright portrays intersectional oppressions to similar effect. Specifically, each play challenges denigrating stereotypes of black women advanced both by the white majority and men within the African American community. As such, in discussing each play, I will emphasize how each playwright uses her portrayal of oppression to challenge historical stereotypes. Secondly, I do not mean to suggest that these plays in particular are unique in exploring intersectional oppression or challenging hegemonic portrayals of black women. Indeed, a more lengthy analysis might address several more examples with similar thematic emphasis. However, given the scope of this essay, I have selected plays which share a core thematic interest but are diverse in terms of the time period in which they were written and in terms of the class, education, and geography of their characters.

To begin, Mary P. Burrill’s drama They That Sit in Darkness emphasizes the great toll inflicted on the body of poor African American women by systems of gendered and racial discrimination. The play’s central characters are Malinda Jasper, a “tired looking [African American] woman of thirty-eight” who struggles to raise and nurture a family of seven children, as well as Lindy Jasper, her seventeen year old daughter who will soon leave to study at the Tuskegee Institute (Burrill, 67). The Jasper family lives in a small home in the rural south. At the start of the play, Malinda has just given birth and has been instructed by her doctor that her heart is very weak. Despite her doctor’s orders, she has left her bed to wash laundry and attend to household chores. From here, the plot proceeds in a straightforward manner: a nurse, Miss Shaw, arrives and orders Malinda to bed while Lindy attends to the children. In the play’s moment of crisis, Malinda succumbs to her heart condition. At the conclusion of the play, Lindy realizes that she must abandon her hopes of receiving an education in order to stay and care for her brothers and sisters.

Despite a relatively simple plot, Burrill’s drama illustrates several multifaceted causes of the Jasper family’s poverty and Malinda Jasper’s illness and death. Throughout the play, Burrill emphasizes the abject poverty of the family. Their small home, the setting of the play, is “dingy” and its low walls are covered with “great black patches as though from smoke” (Burrill, 67). Later in the play, we learn that Malinda has no food to feed her children. When Malinda’s son Miles returns from the store empty-handed, without the bread or milk he was sent for, he states, “Mister Jackson say yuh cain’t have no milk an’ no nothin’ ‘tel de bill’s paid” (Burrill, 69). However, as Malinda states, her husband has given all of his recent earnings to pay doctor’s bills. Thus, the family’s severe poverty forces them to choose between food and essential healthcare.

Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, standard portrayals of African Americans by whites often placed the blame for poverty on the supposed inferiority of African Americans. In performance art, for instance, the American minstrel shows of the mid- and late-nineteenth century often featured white performers clad in blackface. These performances perpetuated the stereotype that African Americans were, “lazy, dumbly guileful, noisy, flashily garbed, but essentially happy” (Bordman and Hischak). Later, these caustic stereotypes were advanced elsewhere, even in the work of many biologists and psychologists who argued spuriously that the supposed inferiority of African Americans had scientific basis. For instance, psychologist Lewis Terman wrote in his 1916 text The Measuring of Intelligence that, “[African American’s] dullness seems to be racial…from a eugenic point of view they constitute a grave problem because of their prolific breeding” (Terman, 91-92). Thus, a dominant cultural narrative (evidenced in both art and science) at the time of Burrill’s writing advanced the idea that African Americans were inherently lazy, unintelligent, and “prolific” breeders. Burrill, on the other hand, presents an analysis of black poverty that shifts the blame from this supposed inferiority to the cyclical oppression which trapped African Americans and, in particular, black women.

In the play, the root of the Jasper’s poverty defies simple, non-structural explanation. Both Malinda Jasper and her husband are tireless workers. Scholar Ann Fox notes that, “Malinda cannot help but work,” and that, “disability is the invisible and direct result of a lifetime’s struggle to support her family” (Fox, 157). Indeed, Malinda not only cares for her children but also has a job washing laundry for white families. Likewise, Malinda’s husband works extremely long days to support his family. Malinda states, “When Jim [her husband] go out to wuk—chillern’s sleepin’; when he comes in late at night—chillern’s spleepin’” (Burrill 71). Despite their seemingly indefatigable work ethic, Melinda and Jim’s family remains destitute. Thus, we must look to structural causes to understand the poverty of the Jasper family.

One of the chief causes of poverty identified by Burrill in the play is a cyclical denial of educational opportunity. This is emphasized by means of the dialectical speech of the characters in the play, which stands in as a marker of race, class, and rural geography. All members of the Jasper family speak in dialect. For instance, Malinda says, “Dis ole pain goin’ be takin’ me ‘way from heah one o’ dese days” (Burrill, 68). In contrast, the well-to-do white (and likely educated) nurse (Miss Shaw) who visits to attend to Malinda speaks in standard English. Though Burrill does not reveal a great deal about Miss Shaw’s background, we can conclude that she is at least sufficiently educated to hold a medical job.

There is, at the beginning of the play, hope that Lindy will leave to be educated at the African American Tuskegee Institute and escape the cycle of poverty. However, as a result of Malinda’s death at the conclusion of the play, Lindy is trapped by the demands of child-rearing. Thus, Burrill emphasizes the cyclical nature of the Jasper’s poverty. Lindy, who is presented as kind, smart, and excited about her educational opportunity, is decidedly not trapped by any inherent "inferiority.” Rather, she is trapped by a vicious cycle of intersectional oppressions. Because Lindy is black (note that Miss Shaw, the only educated character in the play, is white), a woman (she is automatically expected to take up household duties in her mother’s place), and poor (her family’s poverty demands that she stay with them), she will never have the educational opportunity to raise herself out of poverty.

Another chief cause indicated by Burrill is lack of access and knowledge regarding birth control. In the play, Miss Shaw admonishes Malinda for having children frequently. In response, Malinda states, “But what kin Ah do—de chillern come” (Burrill, 71)! However, Miss Shaw notes that the law “forbids my telling you what you have a right to know” (Burrill, 72)! Thus, on a societal level, poor black women are barred from the means (and even knowledge) of contraception that would help them manage their family size. That this was a central focus of Burrill’s work is evidenced by the fact that she first published it in Margaret Sanger’s Birth Control Review, a journal focused on female reproductive choice.

Furthermore, the play emphasizes the negative consequences of having so many children. Aside from poverty, several of the Jasper children experience birth defects. Among the most serious is that of Pinkie, who “warn’t right in de haid” (Burrill, 71). As Malinda describes, Pinkie was raped and impregnated by one of her employers, a white man. Malinda notes that she had no recourse available for the crime committed against Pinkie: “cullud fokls cain’t do nothin’ to white folks down heah” (Burrill, 71). Pinkie’s story illustrates the negative repercussions of having too many children and the lack of legal protection experienced by African Americans.

Thus, They That Sit in Darkness emphasizes the multiple systems of oppression that affected black women, including lack of access to education and to birth control. The different systems of oppression that affect Malinda (and, by implication at the end of the play, Lindy) must be understood in virtue of her blackness and her womanhood. Fox argues that, within the play, “poverty, and the disability resulting from it, are not depicted as the inevitable fate of African Americans but rather as conditions that have been created literally and figuratively by social policy, convention, racism, and sexism” (Fox, 159). Similarly, scholars Julie Armstrong and Amy Schmidt contend that Burrill used her playwrighting skill to, “raise awareness about race and gender issues” (Armstrong and Schmidt, 49). In emphasizing the vicious cycle of oppressions that trap African American women, Burrill directly challenges the cultural narrative that blamed African Americans for their own poverty.

To continue, Alice Childress’s Wine in the Wilderness is in many ways a very different sort of play than Burrill’s They That Sit in Darkness. Structurally and stylistically, the two plays are not overly dissimilar. Though Wine in the Wilderness is considerably longer than Burrill’s short one-act, each is linear, generally follows a climactic structure, and is grounded in a realistic world. However, each play focuses on a radically different aspect of the African American community. Childress’s play is set in 1964 in Harlem, on the night of a race riot. (There is, therefore, a sharp contrast in geography: we have moved from the rural south to the urban north). Bill Jameson, a college-educated artist living in the city, is painting a triptych exploring black womanhood. The first third of Bill’s painting features an innocent young black girl and the second third features an African princess—“regal, black, womanhood in her noblest form” (Childress, 9). Bill has reserved the last third for a low-class woman (as he believes society has molded black women): “…as far from my African queen as a woman can get without crackin’ up…she’s ignorant, unfeminine, coarse, rude” (Childress, 9).

To fulfill Bill’s need for such a model, Bill’s educated friends Sonny and Cynthia bring Tommy, a loud-spoken and sometimes crass black woman whom they met at a bar, to Bill’s apartment. Over the course of an evening, Bill frequently denigrates Tommy until, at last, he begins to appreciate her beauty and the two make love. The next morning, however, Tommy learns that she was to be the model for Bill’s painting of a low-class woman and tensions again begin to rise. At the conclusion of the play, after much argument among Tommy, Bill, and Bill’s friends, Bill at last acknowledges the error of his ways and decides to paint Tommy in order to capture her beauty, not her perceived lack of class. Ultimately, Childress’s play has a key similarity with Burrill’s: each features a central character whose struggle must be understood in virtue of the fact the she is a black woman—not simply black or a woman, independently—and is at the nexus of a complex set of oppressions.

Childress’s decision to set her play on the night of a race riot is critical. The intermittent chaos and gunfire the audience hears outside Bill’s otherwise peaceful apartment is a reminder of the looming specter of American racism and the fight for civil rights. However, this fight is a double-edged blade. While on the one hand it asserts the humanity and dignity of African Americans, its rhetoric often denigrated women on the other. Throughout the play, Tommy is insulted and degraded by Bill and his friends both for her womanhood and for her low-class status. Even Cynthia, Bill’s female friend, casts a critical eye on Tommy: “You’re too brash. You’re too used to looking out for yourself. It makes us lose our femininity” (Childress, 19). Tommy is thus doubly oppressed within her social context: both from outside the African American community (in virtue of her blackness) and from within (in virtue of her class and gender).

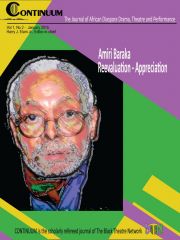

In this regard, I submit that Childress’s portrayal of intersectional oppression operates in a similar but distinct way from Burrill’s. Burrill, I have argued, was interested in challenging the narrative of black poverty advanced by whites. Childress, on the other hand, is interested in challenging a restrictive narrative of black womanhood advanced by black men within the African American community. For instance, scholar Soyica Diggs Colbert points to the misogyny that often marked the Black Arts Movement, an artistic movement which was closely related to the revolutionary ideals of the Black Power Movement and lasted from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s. Colbert notes a specific example: in playwright, poet, and writer Amiri Baraka’s landmark essay “The Revolutionary Theatre”—an essay “central to the conceptualization of revolution as an aesthetic endeavor during the Black Arts Movement”—which called for the “liberation of black manhood” (Colbert, 78). Colbert notes that Baraka argues for, “…heroes [such as] Crazy Horse, Demark Vesey, Patrice Lumumba, and not history, not memory, not sad sentimental groping for warmth in our despair; these will be new men, new heroes…” (Colbert, 78). This vision for revolutionary black theatre is clearly to the exclusion of the black woman.

In Wine in the Wilderness, Bill (and other characters) frequently denigrate Tommy and stereotype black women. For instance, Bill states that, “The Matriarchy gotta go. Y’all throw them suppers together, keep your husband happy, raise the kids” (Childress, 25). Thus, Bill believes that Tommy can only be a proper woman if confined to a very narrow domestic role. Regarding this point, Soyica Colbert notes that, “Bill’s remark, which does not exist in a vacuum but expresses an overriding misconception at the time, serves to demonize black women and position them as the architects of the destruction of the black family” (Colbert, 82). Bill’s denigration of Tommy also attempts to assert his intellectual superiority. In one scene, he quizzes Tommy about famous figures in African American history and lectures her like a child in school (Childress, 23-24). Later, Tommy discusses her rich family history at length, revealing that—although she lacks a formal education—Tommy carries with her a great deal of familial folk knowledge that Bill has overlooked (Childress, 28-30).

At the conclusion of the play, Bill is liberated from his misogynistic ideology by the revelation that Tommy (and, indeed, all of the characters) are worth painting simply in virtue of their own beauty. I contend that this revelation amounts to a newfound ability to see past the symbolic “other” of black womanhood he has constructed in his mind. In other words, he is newly able to see Tommy for her wonderful, individual qualities instead of in a confining, one-dimensional manner. Early in the play, Bill rejects the flesh-and-blood woman in front of him as imperfect in favor of a symbolic, “flawless” African princess that does not correspond to reality. Moreover, a woman, for Bill, should fill a very specific domestic role. Ultimately, argues scholar Josephine Lee, “Alice Childress's Wine in the Wilderness shows the misguided ideals of the artist, Bill, and his other college-educated friends through Bill's worship of his romanticized model of African beauty; it takes the ‘messed-up chick,’ Tommy, to show them the ‘true’ face of black womanhood” (Lee, 77).

In conclusion, an intersectional analysis is critical to understanding Tommy’s character. At the same time African Americans take to the street and riot against racial injustice, they burn down Tommy’s home (literally and metaphorically). Tommy, as has been illustrated, faces multiple and interlocking levels of class, gender, and race-based discrimination. Soyica Colbert concludes that, “Wine in the Wilderness exemplifies the potential and shortcomings of the revolutionary artist: promoting Black Nationalist rhetoric, while simultaneously disparaging women and the working class” (78). In another article, “Dialectical Dialogues,” Diggs again indicates the complex systems of discrimination at work within Wine in the Wilderness: “…Alice Childress’s drama points to the way race comes to stand in for a myriad of power relations, including professional, familial, and communal” (43). Thus, both They That Sit in Darkness and Wine in the Wilderness challenge denigrating cultural narratives regarding black women, though Childress’s drama focuses on a vision of black womanhood advanced specifically by men within the African American community.

Finally, Pearl Cleage’s The Nacirema Society Requests… shifts its focus to an entirely different group within the African American community. Stylistically, like Burrill’s and Childress’s dramas, Cleage’s play is grounded in a realistic world and follows a traditional climactic plot structure. However, in Nacirema Society, we take another step up the class ladder: from abject poverty in They that Sit in Darkness and the educated middle-class in Wine in the Wilderness to the very rich, upper-crust women of the Nacirema Society of Montgomery, Alabama in Cleage’s play. Like Burrill’s play, Cleage’s is set in the south (albeit an urban setting this time). And, like Wine in the Wilderness, Nacirema Society is set in 1964, against the backdrop of the turmoil of the Civil Rights Movement. As in Childress’s play, this struggle is not seen directly by the audience. Rather, the characters discuss an upcoming voter registration drive led by Martin Luther King, Jr. as well as the famous bus boycotts that took place one decade before.

Within this context, the plot of Nacirema Society proceeds in a straightforward manner. The members of the Nacirema Society, all wealthy African American female socialites, are preparing for a celebratory cotillion on their one-hundredth anniversary. Family matriarchs Grace Dunbar and Catherine Adams Green anticipate that their grandchildren—Gracie Dunbar and Bobby Green, respectively—will get engaged at the cotillion. From there, Cleage’s tale becomes much more complicated, due to the arrivals of a critical New York Times reporter, Alpha Campbell (the daughter of a former Dunbar servant who attempts to blackmail Grace), and her daughter Lillie (who is in mutual love with Bobby Green). Ultimately, the plot resolves neatly and happily after we learn that Alpha Campbell is the extramarital daughter of Grace’s late husband and Bobby receives a blessing to marry Lillie.

I submit that Cleage’s traditional style and structure are key to understanding her challenge to historical portrayals of black women. Transplanted from its setting, Cleage’s plot might be at home in an Oscar Wilde drama. Indeed, many of the play’s elements—a focus on marriage and who is “proper,” posturing and pretension by upper class characters, and a final twist which reveals that a lower-class character is a member of a wealthy family—suggest a comedy of manners like Wilde’s Importance of Being Earnest. Given the traditional story tropes employed by Cleage, it may be surprising to suggest that her drama includes a subversive analysis of intersectional oppression dynamics and a challenge to historical stereotypes, but I will argue that this is precisely the thematic core of Cleage’s drama.

To begin: what is the effect of telling a well-worn, Wilde-esque dramatic plot in the context of Montgomery, Alabama in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement, using almost exclusively black female characters? Dramatic portrayals of black women that are wealthy, self-sufficient, and family matriarchs are quite rare (though not non-existent—August Wilson’s Radio Golf comes to mind). Among black female playwrights, one finds few portrayals of wealthy African American families (Lydia Diamond’s Stick Fly is a rare example). However, so far as I can determine, Cleage stands alone among black female playwrights in portraying African American characters who are wealthy, educated, and exclusively female. By setting a comedy of manners in the context that she does and with the characters that she uses, Cleage presents a unique vision which poses an inter-textual challenge to a body of dramatic work that (even among black female playwrights) has largely excluded the possibility of wealthy, self-sufficient black women.

However, Cleage’s critique also goes further than this. By emphasizing a complex set of oppressions, Nacirema Society also poses a challenge to movements for African American equality which denigrate the lower class. Thus far, theatre scholars have yet to devote any critical analysis to Nacirema Society. However, scholars have commented on Cleage’s work as a whole, and several have pointed to Cleage’s interest in sets of intersectional oppression. For example, in the article “The feminist/womanist vision of Pearl Cleage,” scholar Beth Turner writes, “In her articulation of feminist opposition to the interlocking oppressions of sexism, racism, and classism, Cleage’s work resonates with the spirit of Ntozake Shange and Alice Childress” (100). Similarly, in her book Black Feminism in Contemporary Drama, Lisa Anderson states,“Each of her plays combines struggles against racism and sexism; she uses specific historical moments to engage her audience in a moment in black history” (17). I submit that Cleage’s interest in class, race, and gendered oppression holds true in Nacirema Society.

That Pearl Cleage is particularly interested in investigating these systems of oppression is suggested by her chosen title. Note that “Nacirema”—which is “American” spelled in reverse—was first introduced in a famous anthropological paper published in 1956 in American Anthropologist by Horace Miner. Miner’s paper, “Body Rituals among the Nacirema,” describes the habits and practices of Americans in stilted, overly clinical ways (Miner). For example, Miner describes the daily ritual “mouth-rite” and the “holy-mouth-men” that the Nacirema frequently visit (these are tooth-brushing and dentists, respectively) (Miner). Miner’s paper illustrates how the anthropological discourse tends to create an “other” out of the peoples who are described. “Othering,” which emphasizes the differences and deemphasizes commonalities between groups of people, is central to systems of discrimination and is highlighted in Cleage’s play.

How do these systems of discrimination operate within the play? To begin, like Childress, Cleage emphasizes the ongoing struggle for the rights of African Americans in the Civil Rights Movement. Though the struggle never pierces the walls of the Dunbar home in the play (and, indeed, is largely lost upon the wealthy older generation of women), we hear about the prior bus boycotts and the upcoming voter registration drive multiple times throughout the text. It is also important to note that, within the play, the Nacirema Society serves to counter the traditional derogatory narrative about African Americans by the white majority. For instance, Grace Dunbar states:“…class, culture, education, refinement. Those Nacirema white dresses were our suits of armor, our protections from who they said we were and our assertion of who we know ourselves to be. This cotillion…is a way of claiming our rightful place in the world” (Cleage, 47). Nonetheless, the wealth of the Nacirema women doesn’t guarantee equitable treatment. Grace notes, for example, that the New York Times had effectively described her society as, “particularly gifted Chimpanzees [who] had learned to play Chopin” (Cleage, 21).

Cleage’s play also illustrates discriminations that even well-to-do women face. Unlike in Burrill’s drama, the women depicted in Cleage’s play are fortunate to have access to education and are even pressured to do so. Nonetheless, the women in this world are still expected to fulfill certain roles. Gracie, for instance, is expected to marry Bobby Green—a socially “proper” choice. When Grace and Catherine discuss the possibility that their grandchildren might not wish to be engaged, Grace offers, “Too bad this isn’t India. Arranged marriages are legal there” (Cleage, 20). Despite their insistence on the importance of a proper marriage, Catherine and Grace’s marriages have been far from ideal. By the end of the play, we learn that both have had husbands who had extramarital affairs. On the other hand, Cleage also resists portrayals of women as helpless and dependent on men. Her cast of characters (which consists of eight women and one man) features women who are ambitious, well-off, and intelligent.

There is, however, a bitter irony within the play’s narrative. Cleage emphasizes the fact that Grace Dunbar and Catherine Green have largely become blind to the struggle of lower class African Americans. In one particularly absurd instance of the blinding privilege of wealth, Catherine complains about the inconvenience of the Montgomery Bus Boycotts because she was forced to pick up her maid in her husband’s expensive car (Cleage, 19). Thus, in their struggle to resist “othering” by the white majority, the leaders of the Nacirema Society have created an “other” out of the lower class African Americans most vulnerable to oppression.

Cleage most strikingly highlights the unseen struggle of the working class through her inclusion of Jessie, a maid in the Dunbar household. Though we see her throughout the play, answering the door and working around the house, Jessie essentially never speaks. As such, Cleage deprives the character who is potentially most disadvantaged of a voice. This is symbolic of the deafness which the Nacirema women have towards the struggles of the lower class. Indeed, though the Nacirema women certainly do face certain oppressions in virtue of their blackness, their wealth has also distanced them from the immediacy of the Civil Rights movement. It has elevated the Nacirema women themselves but not other lower-class African Americans. While the Nacirema women drive their cars and scoff at the inconvenience of the bus boycott, lower class African Americans who rely on public transportation for their livelihood put their jobs and well-being on the line for civil rights. This social struggle exists just outside the walls of the Dunbar home but is, onstage, embodied only in the silent presence of Jessie.

Ultimately, Cleage presents a complex critique by using the context of a very specific historical moment. Note that both Childress and Burrill set their plays roughly around the time of their writing. On the other hand, Cleage—as scholar Lisa Anderson noted—uses historical moments to engage in conversations about racism, sexism, and (in this case) classism. She both resists stereotypes and illustrates the dynamics of privilege and discrimination that operate outside and within the African American community. Thus, while Cleage shares a thematic interest in systems of oppression with Childress and Burrill, her analysis again points in a somewhat different direction.

In conclusion, Burrill, Childress, and Cleage all illustrate systems of intersectional oppression through their dramas. Among the plays, we see radically different portrayals of African Americans. We move up the economic ladder from extreme poverty in Burrill’s play to extreme wealth in Cleage’s. The plays also feature both early and mid-twentieth century settings in the rural and urban South as well as in Harlem. Despite these varied contexts, each play holds a mirror to society and reflects back the ways in which oppressions interlock for females, for African Americans, and for the poor. In doing so, each playwright is performing an act of resistance. In Burrill’s case, the play shines a light on social injustices and challenges the stereotypes of black inferiority. In Childress’s and Cleage’s case, the plays actively wrestle with and subvert race, gender, and class dynamics that operate within and outside the black community. Ultimately, each dramatist belongs to a continued, rich tradition of black female playwrights engaging with and challenging society through the dramatic form.

Works Cited

Anderson, Lisa M. Black Feminism in Contemporary Drama. Urbana: U of Illinois, 2008. Print.

Armstrong, Julie Buckner, and Amy Schmidt. The Civil Rights Reader: American Literature from Jim Crow to Reconciliation. Athens: U of Georgia, 2009. Print.

Bordman, Gerald, and Thomas S. Hischak. "Minstrel Shows."The Oxford Companion to American Theatre. Oxford University Press, 2004. Oxford Reference. 5 May 2014 <http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195169867.001.0001/acref-9780195169867-e-2138>.

Burrill, Mary P. They That Sit in Darkness. Ed. Kathy A. Perkins. Black Female Playwrights. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1989. Print.

Childress, Alice. Wine in the Wilderness. New York: Dramatists Play Service, 1969. Print.

Cleage, Pearl. The Nacirema Society Requests... New York: Dramatists Play Service, 2014. Print.

Colbert, Soyica Diggs. "A Pedagogical Approach to Understanding Rioting as Revolutionary Action in Alice Childress’s Wine in the Wilderness." Theatre Topics 19.1 (2009): 77-85. Print.

Colbert, Soyica Diggs. “Dialectical Dialogues.” Contemporary African American Women Playwrights. Ed. Philip C. Kolin. New York: Routledge, 2007. 99-114. Print.

Fox, Ann M. "A Different Integration: Race and Disability in Early-Twentieth-Century African American Drama by Women." Legacy 30.1 (2013): 151-71. Print.

Lee, Josephine. "Bodies, Revolutions, and Magic: Cultural Nationalism and Racial Fetishism." Modern Drama 44.1 (2001): 72-90. Print.

Lutz, Helma, Maria Vivar, and Linda Supik. Framing Intersectionality. Surrey, UK: Ashgate, 2011. Print.

Miner, Horace. "Body Ritual Among the Nacirema." American Anthropologist58.3 (1956): 503-24. Web. <https://www.msu.edu/~jdowell/miner.html>.

Terman, Lewis. The Measure of Intelligence. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1916. Print.

Turner, Beth. "The Feminist/womanist Vision of Pearl Cleage." Contemporary African American Women Playwrights. Ed. Philip C. Kolin. New York: Routledge, 2007. 99-114. Print.

David B. Smith is currently a senior at the University of Connecticut. He is pursuing dual B.A.s with honors in Theatre Studies and Philosophy (with a concentration in human rights). During his time at the University of Connecticut, David has dramaturged, directed, and acted in several productions. At Connecticut Repertory Theatre, David's recent dramaturgy credits include: Moliere's The Miser, Spring Awakening, His Girl Friday, and Theresa Rebeck's O'Beautiful. In October 2014, David will direct Alessandro Baricco's Novecento with funding from his university. As a scholar, David is interested in political theatre which illuminates and challenges social conventions. David hopes to continue his studies with a graduate degree in drama and to pursue a career as a theatre artist and educator.