Editorial Notes

“Remembering Amiri Baraka”

Harry J. Elam, Jr

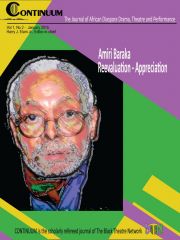

We dedicate this, the second issue of the online journal Continuum to the memory of Amiri Baraka. Amiri Baraka, born Everett Leroy Jones and later known as LeRoi Jones, transformed the fabric of American theater more generally and African American theatre most particularly. He died on January 9, 2014 at the age of 79. Remembered as the “father” of the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, Baraka remained an activist playwright well into the new millennium. Extremely prolific, always provocative, and often controversial, Baraka created a myriad of plays that provoked thought and influenced action. Truly, he understood the power of words and championed the arts not simply as mechanism to delight and entertain but to move people to enact social change. As his political ideology evolved over the course his life—moving through Black Nationalism and onto Marxist Socialism—what remain central and unwavering was his commitment to the cause of Black Liberation and to identifying through artistic expression ways to impact the struggle for human dignity and freedom. In his eulogy, Cornel West pronounced Amiri Baraka, “A literary genius,” “who was willing to reject the white establishment and say ‘I am going to raise my voice.’”(West)

A compelling factor about Baraka and his work was that he continually experimented with structure to support his efforts at “raising his voice.” For Baraka, not only form but content could and should be revolutionary. With persistence, he sought to make form function as the inner logic of content—so that his theatre could not only force change but be change—and this has contributed to his artistic achievement. Too often cultural arbiters have dismissed socially minded artists and their work for being overly didactic or too focused on the immediate context of its creation with little lasting aesthetic value. Yet, Baraka’s work defies such narrow-minded analysis. In its richness of language and style as well as its political commentary, Baraka’s work endures and requires repeated critical examination. Accordingly, the ongoing import of Baraka’s dramaturgy prompts this special issue of Continuum.

Melinda Wilson Ramey, in the opening article for this issue, “Return to The Toilet,” foregrounds the importance of returning to re-examine and re-assess Baraka’s plays not simply in terms of how they contributed to the black past but as to how they inform the present. She studies Baraka’s 1964 incendiary piece, The Toilet that played as part of a twin bill with The Slave. As Wilson Ramey observes, this play challenges its particular social context but also comments on today’s cultural climate. Wilson Ramey discusses how the play points to the connections between demonstrations of power and the assertion of masculinity. As Wilson Ramey reveals the complex intersections of race, masculinity, and sexuality articulated by The Toilet demand considerable unpacking to understand their meanings in 1964 and now.

Susan Stone-Lawrence’s essay “‘A Simple Knife Thrust’: The Complicated Power of Purgative Ritual in Madheart,” also returns to examine the early Baraka and his 1966 play, Madheart, included in his 1969 anthology, Four Black Revolutionary Plays. For Stone-Lawrence, Baraka’s personal evolution in the 1960s—divorcing his white wife and marrying a black one, changing his name from LeRoi Jones to Amiri Baraka—all have a direct correlation to the dramaturgical unfolding of Madheart. In fact, Stone-Lawrence argues that Madheart operates as purgation, a cleansing ritual for Baraka himself as well as for the oppressed black man in America. Stone-Lawrence’s close reading of the play explores the connections of black art for Baraka to avant-garde theatrical practices as well as to social and personal change.

In his essay, “Dramatizing Death Threats: Amiri Baraka’s Nuyorican Trio,” Douglas S. Kern advocates for critics moving away from Baraka’s early canon to engage the later work. Kern explores three plays of the 1990s, Jack Pot Melting: A Commercial, The Election Machine Warehouse, and General Hag’s Skeezag, all first produced at the Nuyorican Poets Cafe Theater in 1996. Through his analysis, Kern draws connections to Baraka’s past revolutionary theater but also Kern articulates how these plays speak to particular issues of their times, such a drug violence. Moreover, Kern shows how these plays incorporate Baraka’s evolving Marxist ideology. He argues that these plays offer a potent view of the threat that American Capitalism offers to proletariat, to people of color and the poor.

As this is a special issue, we have included two special sections. The first is a memoir/remembrance written by Yvette Heyliger, “Parity, Me and Amiri B.”With this autobiographical piece, actor/director Heyliger discusses the influence that Baraka and the Black Arts Movement had on shaping her theatrical coming of age, most particularly in influencing the design of her one person show, Bridge to Baraka. Within her memoir, Heyleger confides that she only gained a deeper appreciation for the Black Arts Movement and Baraka later in life, as she moved into adulthood. The delayed development, she argues enables her to have richer appreciation of the meaning for her of Baraka, most specifically as a woman artist. Now her show, Bridge to Baraka, includes Baraka’s poem, Black Art. In addition, Heyliger now recognizes her voice and her own struggle within the dynamic art and politics of the Black Arts Movement. Heyliger makes an impassioned plea for the importance of activism in art that espouses freedom and equality for all people.

This special issue also includes the three winners of the Black Theatre Network’s S. Randolph EdmondsYoung Scholar Competition for 2014. The graduate winner, Donatella Galella of the City University of New York’s paper is titled, “Playing in the Dark/Musicalizing A Raisin in the Sun.” There are two undergraduate winners; David Smith of the University of Connecticut for his work, “Intersectionality in the Dramas of Mary Burrill, Alice Childress, and Pearl Cleage,” and Anna Waterman of New York University for, “Perceptions of Race in Three Generations of The Jungle Book.” We congratulate them all!

And so the legacy of Amiri Baraka lives on. His theater, his fierce commitment to liberation and activism, his prescience as an artist and thinker will continue to have reverberations in our life times and beyond. Rest in peace Amiri.

Harry J. Elam, Jr.

Works Cited

Cornell West quoted by Anne Correal, “Remembering Amiri Baraka with Politics and Poetry,” New York Times, N.Y/Region Section, 19 January 2014: A26.