Kadogo Runs the Mojo Down:

Bill Harris and Aku Kadogo in Conversation

2015[1]

In reference to Offering 9 – “Kadogo Mojo: global crossings in the theatre”

by Aku Kadogo in Black Acting Methods: Critical Approaches

Abstract

Aku Kadogo met Bill Harris in the 70s when she was a member of Concept East Theatre in Detroit, Michigan. This was a theatre company founded by Woodie King and David Rambeau in the early 60s. She came to know Bill and indeed work with him more recently when she returned to teach at Wayne State University in 2006. Bill, whose poetry, prose, and playwriting have won him acclaim from Detroit to New York City is a compelling storyteller fusing history, music and literary forms. During Bill’s tenure as Kresge Eminent Artist Aku had the opportunity to direct an excerpt from his blues poem/combine novel Booker T and Them (2013). They belong to each other’s admiration society.

| Bill: | Discuss the concepts and realities of displacement and inclusion in your work. |

| Aku: | I find myself “the outsider” in many of my directing situations. Some of that comes from having lived overseas for most of my adult life. In the early days at NAISDA (National Aboriginal/Islander Skills Development Association) in Sydney, Australia, we were privileged to work with many Traditional Owners who came from numerous language groups. This was challenging to my perception of myself as a western educated African American woman. This challenge opened up the gateway to other ways of seeing and a broader vision of myself in the human family. Including ideas and cosmologies that I might not have been familiar with but could inform my own knowledge base: the inclusion of ideas that broadened my spiritual worldview Displacement. This theme is reoccurring for me, especially as we are looking so firmly at global gentrification and dislocation. Maybe we are all displaced. I live in a very fast paced world. I use jets as a mode of transportation. I travel with ease. I expect to travel, but then I also am accustomed to the discomfort of navigating the unfamiliar. Where is home? Where is community? Where is my tribe? The answer for me is: Where ever I’m standing. |

| Bill: | What is the thing in your game that most needs to be strengthened? |

| Aku: | Since I enjoy building original works, I often wish I took more time to build the theatre language for the ensemble I’m working with. I work in a very intuitive manner. Sometimes I wish I were more methodical, but I believe each situation calls for its own approach. I’d like to utilize more time developing physical and emotional language for each individual actor. The truth of the matter is most of the situations I find myself in are short rehearsal periods, leaving little time for strong individual development. I’m good at the big picture but I would love to help individual actors develop more solidly in the style I work in. |

| Bill: | What do you hope is an audience take-away from one of your presentations? |

| Aku: | It is always my intention to have people leave one of my productions thinking about something they might not have thought of before. When I directed Booker T. and Them (an excerpt from your blues novel) I wanted them to think about the beauty of language, the vitality of life during the turn of the 19th century into the 20th. There was Booker T, John Henry and Jim Crow all in the same space together vying for the attention of the audience. There were the visual components we utilized such as a side show circus complete with ring master spruiking. We presented the audience with poetic historical imaginings along with the ideas of an African American man whose legacy lives on today. There were many concepts the audience could latch onto. Movies and television give us so much linear information and I want to challenge our imagination; at least that is my hope. I also want to celebrate the joy in language and visual dexterity. I recently directed Jessica Care Moore’s Salt City: A Techno Choreopoem that takes place in the salt mines of Detroit. The time is the past and future/present. People walked out thinking about salt mines and salt crystals as the set was designed like crystals and we had very beautiful images of salt in its many formations. We see ourselves in the future in this work and that is of the utmost importance to the writer and me. The audience was also given a good dose of techno/house music as created by African American artists. Effectively I am mining our culture to represent us on many fronts. |

| Bill: | What are a couple things you recommend to students interested in theatre? |

| Aku: | When we train students today we know that we are training them for film, television, performance art and stage. It is possible that once they leave the university setting they may not do theatre again. If they are committed to the stage I recommend that they create the theatre that they want to see. I recommend that they make it timely, imaginative and energetic. I suggest they look for alternative spaces in the communities they wish to work in. I also seriously present all my students with the idea of mining one’s own culture to bring forth contemporary tales. |

| Bill: | What are a couple things you warn them against? |

| Aku: | I warn them against getting stuck at thinking only about the financial aspects. Woodie King reminds us of the expense of putting on a theatre production in today’s world. We have to be clever producers as well as directors. |

| Bill: | Ochre & Dust sounds fascinating, but given that there is so little literature about Indigenous people is there a danger that new works created by fusing new and old, will dilute,or threaten the methodology, meaning or importance, or even existence of more traditional works? |

| Aku: | I have witnessed in both Australia and Korea, people grappling with having to keep ancient knowledge alive and relevant for the modern age. And it is a conundrum. My First Nations’ friends find themselves recouping traditional information and presenting it to global audiences. Of course, it is difficult to recreate ceremonial experiences for general consumption. But as we witnessed with the Standing Rock Water Protector[2] movement, many Indigenous people served up healing songs and dances as an antidote to the guns and weaponry meant to protect corporate interests. This is 21st century living theatre. We’re abutting ancient knowledge with rapidly moving technological ‘advances.’ What I understand is that once you actually get to some places in the world, people are moving at a completely different pace and practicing age old customs handed on from generations before them as well as absorbing modern practices. It would seem there is also a serious need to share information the other way around (from the Indigenous perspective) and infuse our ways of seeing from a non-Western point of view. At least we can try. |

| Bill: | What Afrocentric works have been of greatest influence on your understanding of the concept? |

| Aku: | The Wiz (1975), directed by Geoffrey Holder was Afrocentric with its larger than life costume designs, wild imagination, songs, dancing and storytelling, not unlike Duro Ladipo’s Travelling Yoruba Theatre Company’s production of Oba Koso (1972). Ain’t Supposed to Die a Natural Death(1971) by Melvin Van Peebles, directed by Gilbert Moses, and Fela! (2008) directed by Bill T. Jones, along with Will Power’s Flow (2003). These are theatre works that consistently crop up in my head as standards to strive towards. Afrocentric and Afrofuturistic. Uplifting, informative, thought provoking… that’s what Afrocentricism is to me. In the essay I cite a number of musicians. Sun Ra made and continues to make a huge impact on me. The experience of being at a Sun Ra concert was immersive. It was a concert that you might not even understand… you might walk away thinking that you didn’t like the music but you had an experience. An unforgettable, transcendent experience! It is now nearly 40 years ago since I last saw Sun Ra. The Art Ensemble of Chicago, a concert by the Funkadelics and Rahsaan Roland Kirk, also left me with memories similar to Sun Ra. |

| Bill: | Can Afrocentricism and more traditional Western work share a common space? |

| Aku: | I think we already do. To be Afro and not African is already Western. We’re drawing upon a new world experience with a sometimes intuitive or actually realized connection to Africa. Blood memory. Bone memory. |

***

-via Skype May 9, 2015

| Bill: | Reducing 30 pages to 8.[3] Talk about that process. The writer gives you a certain amount of stuff and you edit it. I guess it’s about essence. |

| Aku: | I try to find something in the writing that appeals to me. I read the words and I see action. It might be the rhythm, it might be that I can visualize a highly theatrical scene suggested from the text. I choose the scenes I innately feel something for and attempt to find a through line with those scenes. The choreopoem form is really important to my process, taking disparate scenes that theoretically have nothing to do with each other. Remember, with for colored girls… there were 20 separate poems that seemingly had nothing to do with each other and yet out of that came a full evening’s work of highly charged theatre. |

| Bill: | There are several ideas here. Finding a connection between things even if they don’t exist. That is one of the things you do. Finding a through line, everything is connected. Ultimately everything is connected. I always say everybody is dippin’ out of the same bucket. One of the things I think you do in a universal way is find connections. But you also know who you are and you know where your magnetic north is. You know what rocks your boat. All artists do this. |

| Aku: | I distill the text. I hear it in my own head at first. Then I need to hear the actors read it aloud. I make more cuts. I’m trying to hear what the audience will hear only one time. Will it have an emotional impact? Can I make it more visual? Is it possible to do away with the words? Then I attempt to find a universal through line that makes sense to me and ultimately to my performers. This may never appear linear to the audience and it shouldn’t, but we (the ensemble) have to agree on our performed logic. It is putting a quilt together of images and words; you can take a disparate set of visual and word cues to make a single statement. The director is also the ears and eyes of the audience, who will not have the intimate relationship as the one we have in the rehearsal room. I am the barometer for work. But that’s where the collaboration process is important because your collaborators might see ideas you’ve left out or scrimped on and can guide the work. I like collaborating with the actors as well, because if it isn’t working organically for them then it’s imperative to hone the work towards the truth for the performers. |

| Bill: | Do you have a sense of how you got to what ‘rocks your boat’? How you got to the essence of what it is that moves you? |

| Aku: | My recent return to Detroit (and subsequent continued relationship with the city of my birth) after living away from there for more than 30 years revealed who I think I am at my core and how I came to be this way. I so love the memories of what I thought of Detroit and my childhood… the great beauty of the rituals of community and street life. We don’t have that same community feeling in American cities much any more. But I remember the vitality of Dexter Ave. and that memory fills me with nostalgia while energizing me at the same time. In the essay, I cite many music experiences from my youth. Seeing James Brown, The Parliament-Funkadelics, Ike and Tina Turner, Sun Ra, The Art Ensemble of Chicago and Cecil Taylor dancing around the piano. These musicians exuded everything; visuals, music, poems, dancing and participation from the audience. They took you to a place in your imagination, a place you could transform into your own experience. Seeing those groups was a pure energetic, transformative, memorable happening. I feel that I don’t experience enough of these holistic performances today. I’m always looking for that imaginative, collective, experiential theatre moment. The two years I spent in South Korea I came close to having this on a regular basis. I couldn’t speak the language, so the sound of the language was like music and I had to rely on what I saw, making up a good portion of what I thought that might be. My imagination was totally enlivened. I laughed a lot. I loved that. Sharing laughter, sharing our silences, sharing our awe. They were quite special experiences. I have resided in Australia since 1978, so over half my life I’ve spent with Indigenous people. I’ve experienced ceremony, songs, dances, funerals, and play time through dance and ritual. In the 80s and 90s we were out in remote regions of the country, visiting communities where they intentionally were fortifying their cultural practices. These practices have been revitalized in the ensuing years. I’m accustomed to having song, dance and story with a connection to the cosmic force as a constant force that reoccurs around me. |

| Bill: | The essence of theatre is that in some way or another. What is your definition of theatre? |

| Aku: | There is a quote by the late saxophonist and clarinet player Eric Dolphy, “When you hear music, after it’s over, it’s gone, in the air, you can never capture it again.”[4] It’s the ephemeral. Being in a space where something takes place then tapping into one’s emotions, becoming enlivened by the unnamable and unknowable. |

| Bill: | One of the first poems I ever wrote used that quote! It’s childlike. Not childish, but childlike. Something comes back to childlike enchantment. Being in the moment. That’s what joy is, what theatre is. |

| Aku: | My favorite performance venue doing for colored girls… was the New Federal Theatre. We were so close to the audience. We could hear the laughter and the tears. The audience spoke to various scenes happening on the stage. I loved the proximity and the participation. The audience felt comfortable to participate in the shared experience. Now we are combating the hand-held devices and our audience’s desire to be in two places at once: where we are and with someone through the virtual space. |

| Bill: | There is less a sense of community. Everybody is staring into this device. Everybody is trying to be somewhere other than where they are. The theatre is going have to re-discover that sense of community. We have to get back to people sitting together in the dark, concentrating on the same thing at the same time. The choreopoem can utilize melodramatic techniques, can be silent film and puppet show, can be a poetic distillation where all things are possible. |

| Aku: | We have to captivate the audience again with imaginative experiences. The challenge of working with poetry is that the audience hears the poetry once so the action on stage has to serve as a guiding force. The choreopoem is the perfect tool to merge gesture, word, song and dance, offering the audience many ways into the work. We have big work to do. I know when I’m in those spaces where the music or the storytelling takes you higher that at our truest center we fundamentally need those shared human experiences that only happen when we are together. |

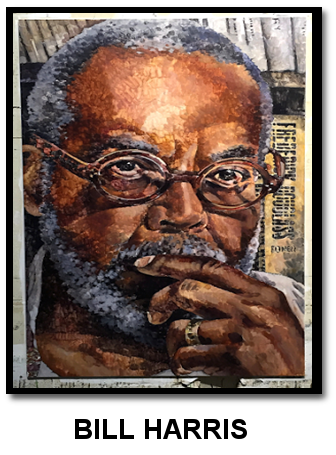

Bill Harris is Emeritus Professor of English at Wayne State University. He is a playwright, poet, and arts critic. He formerly served as artistic coordinator at JazzMobile, and the New Federal Theatre in New York, and was Chief Curator at the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History in Detroit. His plays have been produced nationwide, and he has published books of plays, poetry, and reappraisals of American history. Booker T. & Them: A Blues is his latest publication. He received the Kresge Foundation Eminent Artist award for 2011. Bill states that "[He loves] working with Aku because she brings a special, wide ranging combination of energy, theatrical and cultural knowledge, curiosity, determination and, perhaps, most of all, she "gets it." She understands that everything [they] do is always about the enrichment of the lives of the audiences that we serve."

Aku Kadogo is Chair of the Department of Theatre and Performance at Spelman College after serving as Distinguished Visiting Professor in 2014. She has had an extensive career as an international theatre director, educator, choreographer and performer, creating works in Australia, Korea, Europe and the United States. She has been an Associate Choreographer on RENT touring Australia, China and the United States. As a performer Kadogo has worked in film, television and stage, making her career debut in the original Broadway production of for colored girls who considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf.

NOTES

[1] There were two parts to this interview. Part one: these questions were delivered by email and I answered back via email sent to me April 14 then answered by April 24, 2015. The second part of the interview took place via Skype on May 9, 2015.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dakota_Access_Pipeline_protests. The Dakota Access Pipeline protests, also known by the hashtag #NoDAPL, are grassroots movements that began in early 2016 in reaction to the approved construction of Energy Transfer Partners' Dakota Access Pipeline in the northern United States.

[3] I directed Booker T and Them by Bill Harris in February 2013. I edited the script from his novel Booker T & Them: A Blues. Salt City by Jessica Care Moore premiered at Spelman College on April 25, 2015. I edited 30 pages down to about an 8-page script to present a 30 minute work in progress.)

[4] Audio quote taken from the internet. Jazz-quotes.com